Steve Jobs. Reid Hoffman. Stuart Butterfield.

The tech rockstars behind Apple, LinkedIn, and Slack.

And some of the best programmers the world has ever known, right?

Wrong.

Would it surprise you to know that they studied Calligraphy, Symbolic Systems, and Philosophy, respectively?

Which should really come as no surprise at all when you think about what makes their companies succeed.

After all, do you love your iPhone because it runs more advanced code than Android? Are you a LinkedIn member because the site’s search algorithm is highly efficient? And are you addicted to Slack because it’s built with the most cutting-edge language?

Nope. Chances are you’ve never thought about any of those things. But I’m virtually certain that the following have occurred to you:

Checking your voicemail on the iPhone is a million times easier than on your old flip-phone (“Press * to access your messages. Beep. Now enter your password… You do remember your password, don’t you?”)

Learning about the person who’s going to interview you tomorrow is a million times easier on LinkedIn than by scraping up digital breadcrumbs across the Internet (“Hmm… Looks like she ate a bagel for breakfast yesterday on Twitter, is a fan of Kenny G on Facebook, and once posted on a forum for owners of elderly chihuahuas…”)

Finding that Excel file from seven months ago is a million times easier on Slack than searching through Outlook, your hard drive, and the company network (“I know I had it in here somewhere. Did I email it to Jim in Accounting… or was that Jim in Finance???”)

In each case, technology makes your life easier. But it’s not the technology itself that adds value beyond the previous solution. After all, the previous solutions were all technological in nature, too. Instead, the real value-add comes from the unique insight about you, the user.

And that’s where the liberal arts come in.

Because while engineering might be a great discipline for learning how systems work - i.e., how to write a script in Objective C that converts a line in a voicemail database to a clickable object on-screen - liberal arts is a great discipline for learning how humans work.

Whether your training is in psychology (why do our brains work the way they do?), education (why do our brains learn the way they do?), or philosophy (why do our brains exist at all?), the liberal arts teach you to appreciate the unique way that our species processes the world, not just the most logical way.

Let’s go back to that iPhone example. As groundbreaking a feat as visual voicemail was in 2007, seen through an engineering lens, it wasn’t necessarily a critical feature at all. After all, the existing user path for voicemail already represented a highly logical system - dial a number to access the voicemail database, press a button to request your messages, enter in your password to maintain security. But to an astute psychologist, teacher, or philosopher, this system, though logical, fails a number of fundamental human biases:

We’re impatient: Even three steps is too many when we want information now.

We’re forgetful: Six measly digits might not seem like much to a computer with a 1-terabyte hard drive. But to our frail human brains, swamped with anniversaries to remember and errands to run, that’s six arbitrary digits too many.

We’re subjective: We don’t want to consume information in the order it was received - we want to hear that voicemail from last night’s hot date before listening to Grandma’s message.

And so it takes a humanistic, liberal arts perspective to conceive of such a system in the first place. Moreover, it certainly took incredible human-centered skills to get it implemented. While the coding involved in visual voicemail may not have been rocket science, convincing executives at AT&T to relinquish their stranglehold on voicemail data required deep understanding, relationship-building, and persuasion - all hallmarks of the humanities and social sciences.

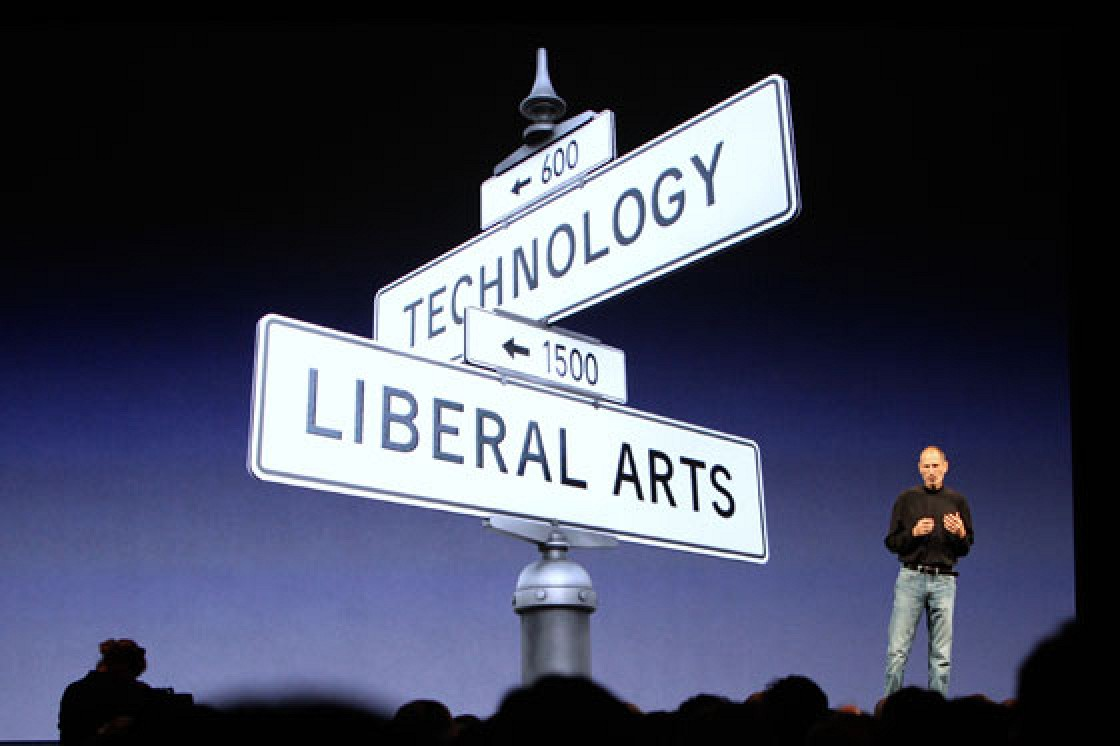

So it’s no wonder that when Steve Jobs later introduced the iPad, he said this: “Technology alone is not enough—it’s technology married with liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields us the results that make our heart sing.”

And, believe it or not, there are now more liberal arts majors working in the US Internet industry than computer science majors. And that’s just counting five non-technical degrees:

Because as valuable as engineers are, at the end of the day, every single tech company is still making products for people. And until we rewire our minds to work as efficiently as an engineer’s schematics, we’ll still need psychologists, teachers, and philosophers to understand, design for, and persuade those beautiful, fallible human brains of ours.

Which means that the next time you find yourself surrounded by philosophers, symbolic systems majors, or, yes, even calligraphers, take a good look. One of them just might be the next Stuart, Reid, or Steve - the next tech rockstar to rock our very human world.