The End of Everything

Every day, a new headline proclaims: “The end of offices!” “The end of handshakes!” “The end of meat!!!”

With everything changing so fast, it's easy to assume that today's trend will become tomorrow's status quo.

But how do we know which of these trends is actually likely to stick after the pandemic ends?

To cut through all the crisis-induced hype, I’d like to propose a three-step forecasting process that's rooted in historical patterns and enduring human desires, not just today's need for a juicy headline...

Step 1: Recognize that Some Trends Are Temporary

We’re all familiar with the idea that big world events lead to big world changes.

Whether it was the Great Depression leading to improved social safety nets, World War II giving rise to the United Nations, or the Great Recession paving the way for the gig economy, it seems obvious that crisis-driven trends can quickly harden into our everyday reality.

But what about all the trends that didn't stick?

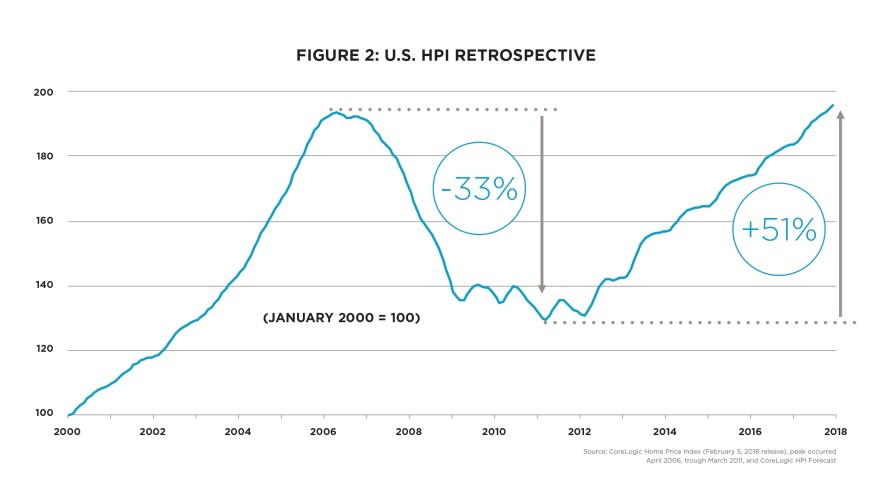

Take the Great Recession for starters. Sure, in 2008, it seemed like we had all learned a painful lesson about the dangers of buying expensive homes we couldn’t really afford. But look what happened to home prices just 10 years later:

Or maybe in the midst of World War II, the temporary rise of Victory Gardens suggested a new golden age of American agricultural self-reliance. But compare that to the sustained rise of the supermarket after the war...

And while the Great Depression may have spurred on low-cost entertainment options like dance marathons, pole-sitting, and goldfish-swallowing, these all (thankfully!) proved to be little more than fads when the world changed again.

So don’t buy the argument behind all those headlines, that a temporary trend is necessarily a permanent one.

We've all just seen the world change fast these past few months. So we know it can change again.

Step 2: Focus on the Underlying Desire

While trends may come and go, human desires tend to be steadfast over millennia.

Food, shelter, love. Not even the most earth-shattering crises can alter those constants.

Which means that instead of focusing on the new trend itself, we should compare it to the underlying desire it seeks to satisfy. And, specifically, we should do it through the Econ 101 lens of substitutability:

Does this new trend ultimately satisfy the underlying desire better or worse than competing goods or services?

An Example: Goldfish-Swallowing vs. Hollywood

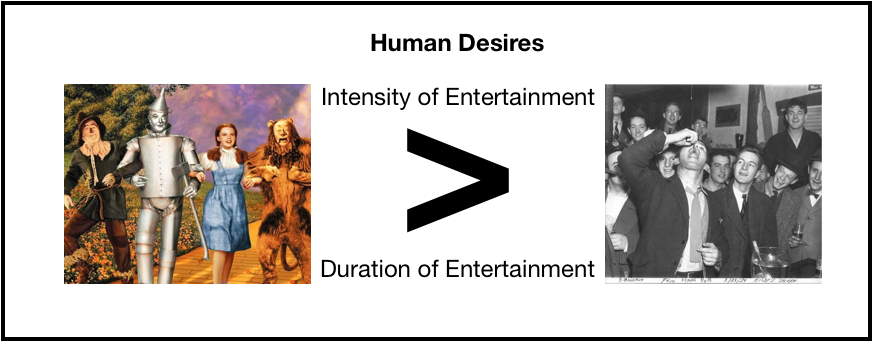

For example, think about the foundational human desire to be entertained. Even in the midst of the Great Depression, the fear of boredom never went away. Which paved the way for those goldfish-swallowers and pole-sitters.

But because this desire can best be expressed as a function of the intensity of the entertainment (all things being equal, you’d rather feel more excited/amused/engaged) and the duration of the entertainment (an hour’s pleasure trumps a moment’s diversion), it’s also no wonder that goldfish-swallowers couldn’t compete with the rise of Hollywood (offering more intense and long-lasting entertainment) as people started to get a little more disposable income back in their pockets.

So it’s fair to say that goldfish-swallowing contests proved to be a poor substitute for other forms of entertainment - thereby limiting their permanence (gross YouTube videos, notwithstanding!).

Another Example: Nylon vs. Silk

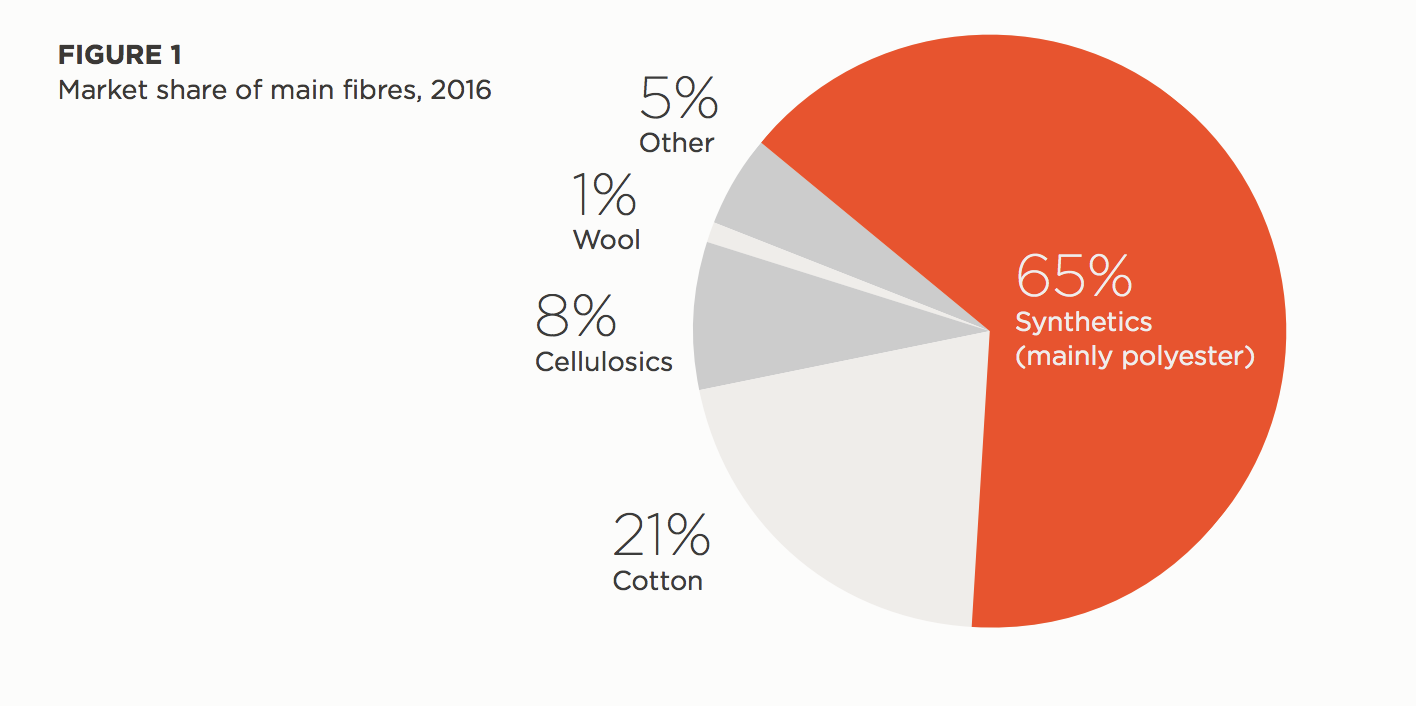

To see the alternative possibility in action - a new trend providing an even better substitute for an existing one - let’s look at another product of the Great Depression: The rise of synthetic fabrics.

If you had told someone at the start of the 1930s that mankind would build a better fabric than silk by the end of the decade, they likely would have laughed you off. After all, silk satisfied so many of our desires: To stay warm, to feel good, to look good. And yet the invention of nylon in 1938 actually served those hungers even better: It could be warmer, more colorful, and less wrinkle-prone. All while lasting longer and costing less!

So synthetic fabrics were actually a superior substitute for many of our desires. And the result is that they still make up a majority of our wardrobe, even to this day.

Step 3: Compare the Substitute to the Desire

To apply this approach to current trends, you only need to identify two factors:

What is the underlying desire that a new trend addresses?

How well does this trend satisfy the desire relative to existing ones?

To demonstrate, let’s look at three of the biggest trends being discussed today:

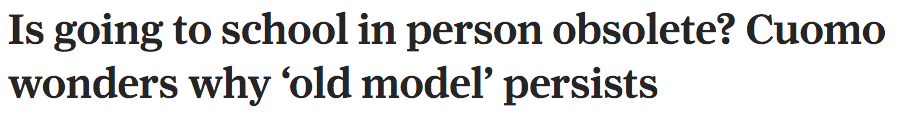

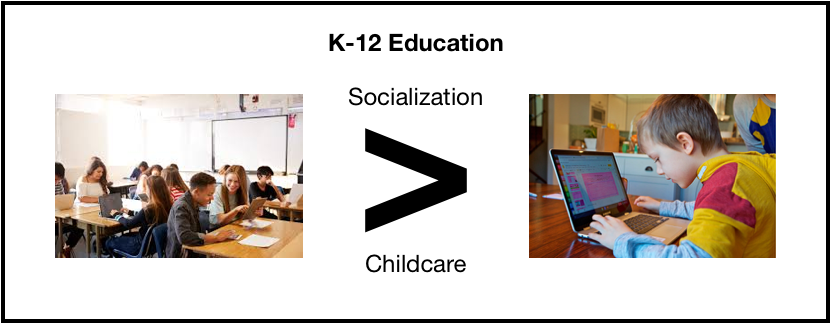

1) Will K-12 Remote Learning Replace In-Person Learning?

Faced with figuring out a way to reopen schools, New York Governor Mario Cuomo asked this question last week:

To answer Gov. Cuomo’s question, let’s start with a couple of the fundamental desires underlying K-12 education:

We want to transfer knowledge to the next generation

We want to socialize young people to become good citizens

We want to free parents up to be productive workers themselves

And now, let’s look at how well remote learning serves these desires relative to in-person learning:

Learning: The evidence is mixed - remote learning may very well be more effective for some students (e.g., those struggling with in-person distractions) and less for others (e.g., those with less access to technology)

Socialization: However, it’s clear that remote learning has been less social and community-building than its in-person counterpart

Childcare: And it’s especially clear that remote learning has been torturous for working parents!

So it feels highly unlikely that K-12 remote learning will persist in a significant way after the crisis ends. It’s just a poor substitute for the multiple desires education must satisfy.

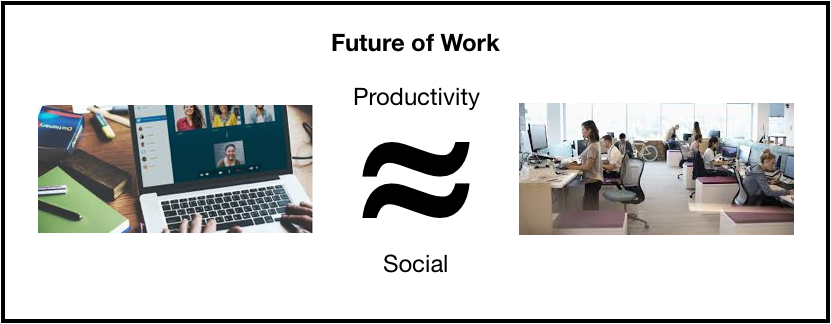

2) Will Remote Work Replace Offices?

While remote learning has received mostly negative feedback from the beginning of the crisis, remote work seems to be more evenly polarizing.

For every headline that proclaims the dawning of a golden new era...

...there’s another one that just can’t wait to get back to the office:

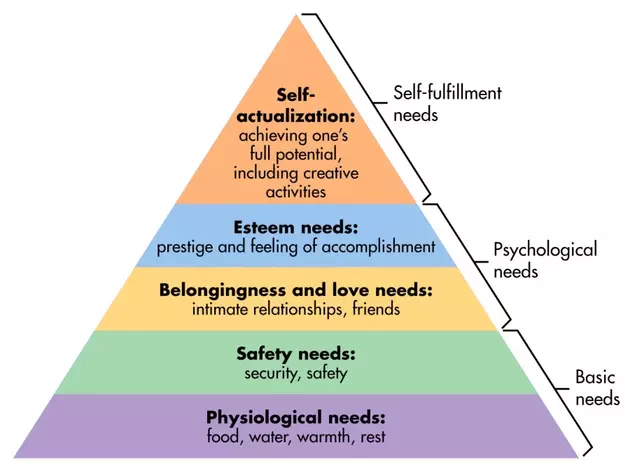

And that comes down to the fact that, unlike education, we all work for different reasons:

For compensation

For stability

For social connection

For ego/pride

For self-actualization

In fact, Maslow’s entire Hierarchy of Needs is reflected in the gamut of what draws us to the labor force.

So it’s pretty clear that remote work is a great substitute for certain needs:

Compensation - Remove long, expensive commutes and you net more money in less time

Self-Actualization - Less watercooler chat means more time to do great things

Whereas it may be a poor substitute for others:

Stability - It could be harder to find work/life balance if you now live at the office

Social Connection - Zoom happy hours might have all the obligation of the in-person version but none of the actual fun

So it’s no surprise that the companies that have committed to a remote working future are the tech firms that attract workers driven by high pay and the chance to build cool things. For their employees, remote work could be a massively improved substitute over commuting for hours in the Bay Area.

But for many employees with different priorities, remote work may go back to being a novelty after the crisis - like Victory Gardens or goldfish-swallowing. In other words, it may be an option if you really want it - but who wants something that doesn’t really meet your needs?

3) Will Grocery Delivery Replace In-Person Shopping?

Perhaps the most consistent trend headline of the crisis has been this one:

And that’s because, unlike remote learning or remote working, remote grocery ordering actually hits many of the key desires behind why we shop:

We need food to survive - Now get food fast, with less effort

We like a wide selection of foods - Get a wider selection than any one grocery store could ever offer

We like to get a good deal - Sort through all the options faster than ever to find the best price

Of course, there are a few desires that grocery delivery can’t satisfy (e.g., touching the produce, chatting with neighbors) but I’d argue that those are niche desires relative to the ones described above.

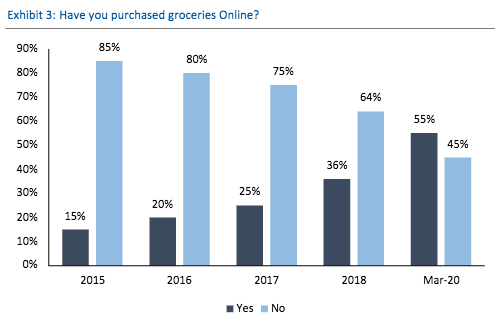

So with grocery delivery having finally cracked a majority of American households this spring (i.e., a tipping point where it no longer feels weird to embrace), I’d suggest that it may be one of the few pandemic trends that will still enjoy widespread adoption after the pandemic.

Follow the Steps… Not the Trends

Now, it may seem premature to make these forecasts just a few months into this crisis. After all, who could have predicted everything that's transpired in just these last couple months alone?

But remember that the key isn’t to focus on what’s changing around us. Instead it’s to focus on what’s staying the same - namely, the desires that have driven us for thousands of years.

And then, with a firm sense of the societal strike zone (i.e., does this new trend actually fit our permanent desires - or just our temporary needs?), you can make the final call on what will stick. And what will become just another goldfish to swallow… :)